According to a study published in Scientific American and the journal American Anthropologist, women were also hunters during the palaeolithic period.

The well-known narrative, that men had the role of hunters, while women primarily engaged in gathering activities has led us to believe that roles were determined by gender. The differing anatomies of men and women often rendered hunting a challenging task for women. Consequently, the role of hunters in human evolution was predominantly led by men.

The theory of men as hunters and women as gatherers first gained notoriety in 1968, when anthropologists Richard B. Lee and Irven DeVore published Man the Hunter, a collection of scholarly papers presented at a symposium in 1966.

However, researchers from the University of Notre Dame have examined the division of labour according to sex during the Palaeolithic era, approximately 2.5 million to 12,000 years ago. Upon a thorough examination of contemporary archaeological findings and literature, the researchers discovered limited substantiation for the notion of distinct gender-based roles.

The team also scrutinized female physiology and observed that women exhibited physical capabilities suitable for hunting, along with scant evidence suggesting their exclusion from hunting activities.

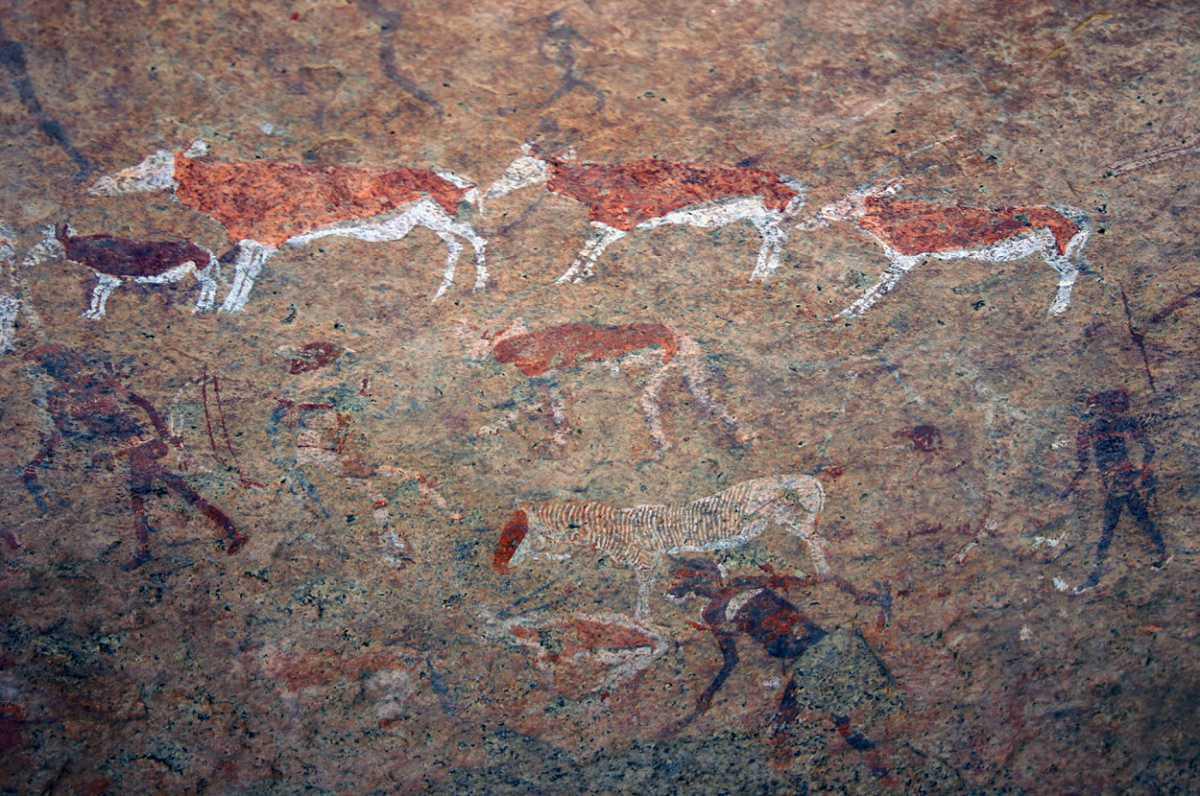

The investigators identified instances of gender equality in ancient artifacts, dietary practices, artistic expressions, burial customs, and anatomical characteristics. “But from what evidence we do have, there appears to be almost no sex differences in roles,” said Sarah Lacy from the University of Delaware.

The researchers also questioned whether anatomical and physiological distinctions between men and women posed limitations on women's hunting capabilities. Their investigation revealed that men possessed an edge over women in endeavours demanding speed and power, such as sprinting and throwing.

Conversely, women held an advantage over men in pursuits necessitating endurance, like long-distance running. This is supported by he fact that estrogen can increase fat metabolism, which gives muscles a longer-lasting energy source and can regulate muscle breakdown, thus preventing muscles from wearing down. Scientists have traced estrogen receptors, proteins that direct the hormone to the right place in the body, back to 600 million years ago.

“When we take a deeper look at the anatomy and the modern physiology and then actually look at the skeletal remains of ancient people, there's no difference in trauma patterns between males and females, because they're doing the same activities,” said Professor Lacy.

The study concludes that for 3 million years, men and women both participated in subsistence gathering for their communities, and dependence on meat and hunting was driven by both sexes.