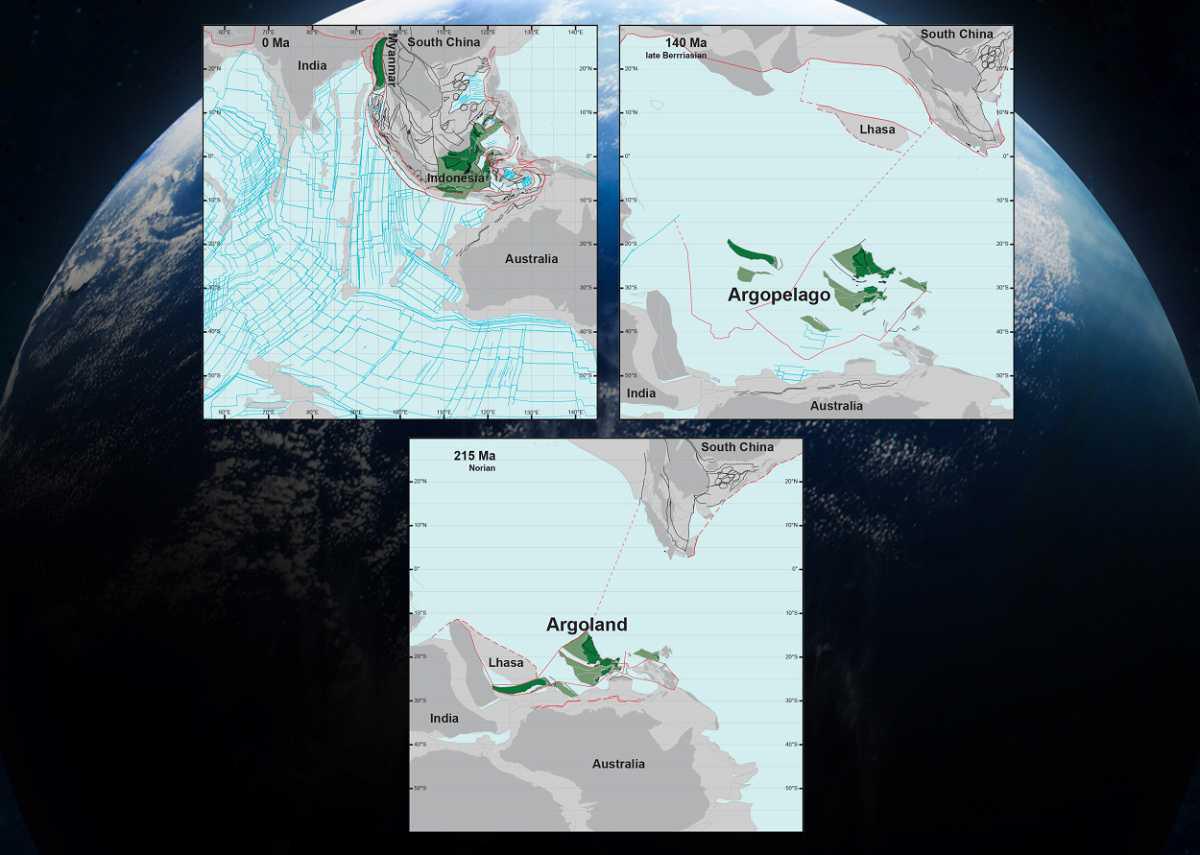

Approximately 155 million years ago, a 5000 km piece of continent broke off from western Australia, leaving behind a basin hidden below the ocean known as the Argo Abyssal Plain.

This underwater feature lends its name to the newly formed continent of Argoland, which must have drifted to where the islands of Southeast Asia are located today. A study of the region yields no evidence of a large continent hidden beneath the islands, only remnants of small continental fragments which has become a geological puzzle.

Geologists at Utrecht University have now managed to reconstruct the history of the lost continent. As it turns out, Argoland is in fragments, but is still there. “Otherwise, we would have been faced with a major scientific problem.”

Geologists distinguish the Earth's crust into two primary types: the denser oceanic crust and the less dense continental crust. These less dense continental landmasses can sometimes extend below sea level, much like the scenario with another "vanished" continent, Greater Adria. Similar to Argoland, Greater Adria was comprised of various fragments isolated by narrow ocean basins, which later merged into a single tectonic plate.

At a certain point in the past, Greater Adria subducted into the Earth's mantle leaving its upper layer behind, resulting in the formation of the mountain ranges in Southern Europe. In contrast, Argoland did not leave any evidence in the form of folded rock layers.

“If continents can dive into the mantle and disappear entirely, without leaving a geological trace at the earth’s surface, then we wouldn’t have much of an idea of what the earth could have looked in the geological past. It would be almost impossible to create reliable reconstructions of former supercontinents and the earth’s geography in foregone eras”, explains Utrecht University geologist Douwe van Hinsbergen.

“Those reconstructions are vital for our understanding of processes like the evolution of biodiversity and climate, or for finding raw materials. And at a more fundamental level: for understanding how mountains are formed or for working out the driving forces behind plate tectonics; two phenomena that are closely related.”

The next question Van Hinsbergen wanted answered is what the geology of Southeast Asia could tell about Argoland’s fate. “We were literally dealing with islands of information, which is why our research took so long. We spent seven years putting the puzzle together”, says Advokaat.

“The situation in Southeast Asia is very different from places like Africa and South America, where a continent broke neatly into two pieces. Argoland splintered into many different shards. That obstructed our view of the continent’s journey.”

However, this changed when he recognized that the fragments had reached their present positions at approximately the same time, shedding light on their prior connections. These broken pieces came together like a mosaic, with Argoland concealed beneath the lush jungles spanning significant areas of Indonesia and Myanmar.

This kind of fragmentation is a characteristic feature of the microcontinent. Argoland was never a singular, well-defined, and cohesive continent; instead, it resembled an "Argopelago" consisting of microcontinental fragments separated by ancient oceanic basins. In this respect, it shares similarities with Greater Adria, which has mostly subducted into the Earth's mantle by now, or Zeelandia, the predominantly submerged continent located to the east of Australia. “The splintering of Argoland started around 300 million years ago”, Van Hinsbergen adds.

The puzzle that Advokaat and Van Hinsbergen have solved fits seamlessly between the neighbouring geological systems of the Himalayas and the Philippines. Their detective work also explains why Argoland is so fragmented: the break-up accelerated around 215 million years ago, as the continent shattered into thin splinters.

The geologists conducted field work on several islands, including Sumatra, the Andaman Islands, Borneo, Sulawesi and Timor, to test their models and determine the age of key rock strata.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2023.10.005

Header Image Credit : Utrecht University