Scientists have established a connection between the travels of a 14,000-year-old woolly mammoth and the oldest known human settlements in Alaska.

Using an isotope analysis, the researchers studied the tusk from a female mammoth nicknamed “Élmayųujey'eh” (Elma), which was found at the Swan Point archaeological site in Interior Alaska.

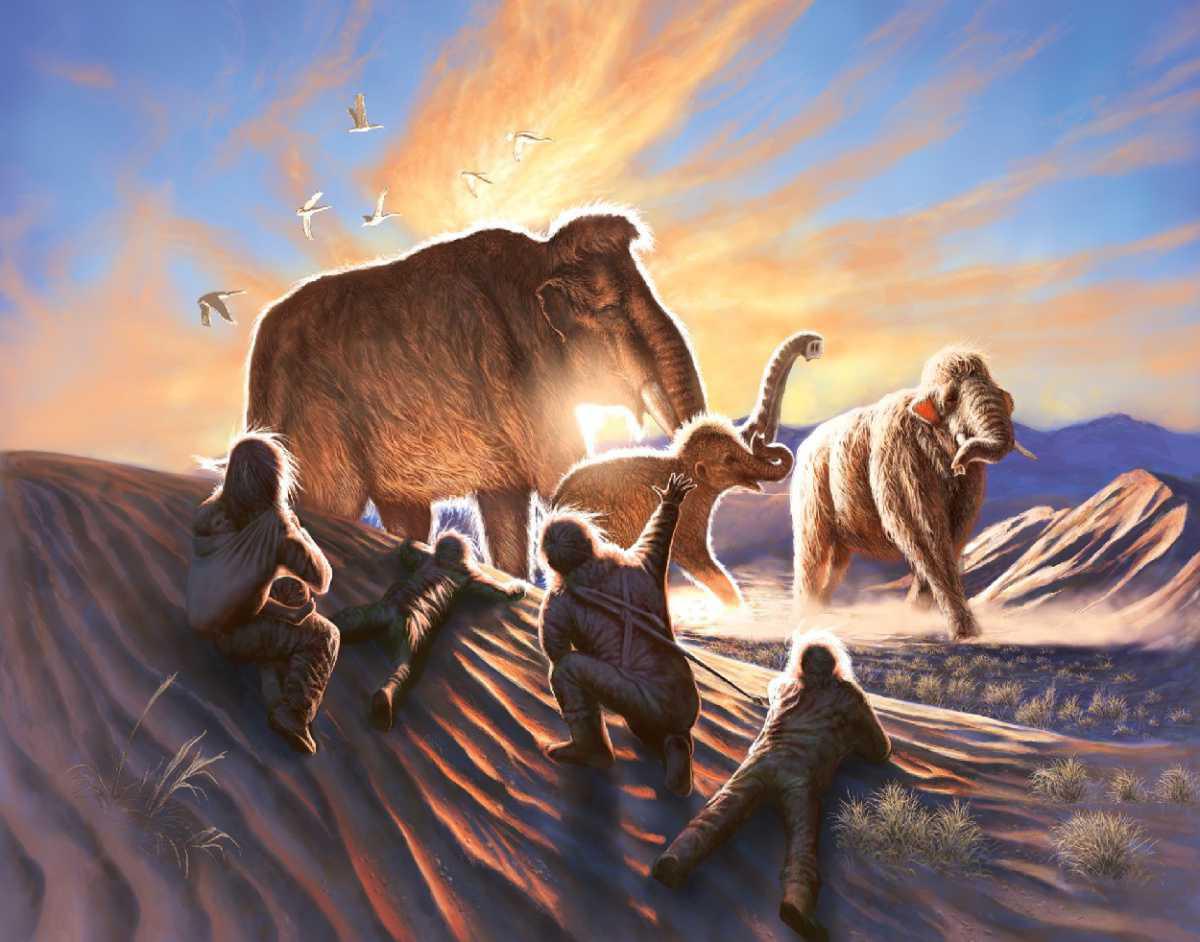

Alongside Elma's tusk, excavations in 2009 also discovered the remains of two related juvenile mammoths, evidence of campfires, the use of stone tools, and butchered remains of other game. Ben Potter, an archaeologist and professor of anthropology at UAF, noted that all these findings "indicate a pattern consistent with human hunting of mammoths."

According to the researchers, the study has provided new insights into Elma's 1,000-kilometer journey through Alaska and northwestern Canada, in addition to the relationship with some of the earliest people to traverse the Bering Land Bridge.

Isotopic data, coupled with archaeological evidence, and DNA from other mammoths found at Swan Point suggest that early Alaskans planned their settlements to coincide with areas where mammoths gathered.

“She wandered around the densest region of archaeological sites in Alaska,” said Audrey Rowe, a University of Alaska Fairbanks Ph.D. student and lead author of the study published in the journal Science Advances. “It looks like these early people were establishing hunting camps in areas that were frequented by mammoths.”

These findings offer proof that mammoths and early hunter-gatherers shared habitat in the region, as the enduring and predictable presence of woolly mammoths would have attracted humans to the area.

Researchers at UAF's Alaska Stable Isotope Facility then extensively analysed thousands of samples from Elma's tusk to reconstruct her life and travels. Isotopes serve as chemical markers, revealing an animal's diet and location. These markers are preserved in the bones and tissues of animals, persisting even after their death.

Mammoth tusks, growing throughout the ancient animals' lives, feature clearly visible layers when split lengthwise, making them ideal for isotopic study. These growth bands enable researchers to create a chronological record of a mammoth's life by studying isotopes in samples along the tusk.

Elma's journey significantly overlapped with that of a previously studied male mammoth living 3,000 years earlier, showcasing long-term movement patterns by mammoths over several millennia. In Elma's case, the isotopic analysis also indicated that she was a healthy 20-year-old female.

“She was a young adult in the prime of life. Her isotopes showed she was not malnourished and that she died in the same season as the seasonal hunting camp at Swan Point where her tusk was found,” said senior author Matthew Wooller, who is director of the Alaska Stable Isotope Facility and a professor at UAF’s College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences.

The time during which Elma existed could have seen the intensified difficulties arising from the relatively recent presence of humans. The steppe landscape, previously dominated by grass and shrubs in Interior Alaska, was also undergoing a transition toward a more forested terrain.

“Climate change at the end of the ice age fragmented mammoths’ preferred open habitat, potentially decreasing movement and making them more vulnerable to human predation,” said Professor Ben Potter.

Header Image Credit : Julius Csostonyi